How C.S. Lewis’s forgotten masterpiece reveals the cost of living behind perfection and the freedom of finally facing ourselves.

I’m sure most Penn students feel inundated with talk about Penn Face by now. Endless panels, wellness seminars, and workshops on the topic have made it almost more myth than menace; a familiar ghost we’ve learned to live with. By the time I graduated, the phrase had begun to sound rehearsed, a word we used to signal awareness without ever breaking the spell itself.

Still, the truth of it remains. Beneath the surface of smiling faces and full calendars lies the quiet fatigue that comes from living as a performance. The late-night grind becomes a kind of ritual; the exhaustion, a badge of honor. We learn to speak of balance and wellness while secretly measuring our worth by how little we sleep.

It took me years— and a book— to understand why that mask felt so heavy.

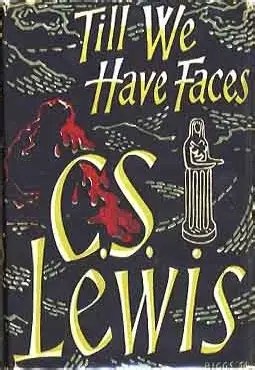

James Baldwin once wrote, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.” There is a kind of humility in that insight: that reading collapses the distance between our private struggles and the human story at large. It was through C.S. Lewis’ Till We Have Faces that I came to understand Penn Face in that same light; not merely as a local cultural problem but a universal and spiritual crisis of self-knowledge— a forgetfulness of who we are before God

Lewis’ novel reimagines the Greek myth of Cupid and Psyche, telling it from the perspective of Orual, Psyche’s older sister and later the Queen of Glome. When Psyche is chosen as a divine sacrifice to a god she cannot see,Orual’s possessive love drives her to demand proof of his existence; to insist that Psyche look upon the god’s face, violating the singular command she had been previously given. The act destroys Psyche’s happiness and condemns Orual to years of guilt. In her grief, Orual hides her ‘disfigured’ face behind a veil and devotes herself to rule, achievement, and duty. She becomes powerful and admired as the queen— yet also hollow within. Her veil protects her from judgment but also estranges her from herself. “The Queen of Glome had more and more part in me and Orual less and less,” she says. “It was like being with child, but reversed; the thing I carried in me grew slowly smaller and less alive.”

All manner of masks or coverings appear in the novel: from Queen Orual’s veil to the High Priest’s bird mask to the painted faces of the priestesses of Ungit. The priestesses, especially, wore masks not of wood or of cloth, but ones made of powder and paint. This excessive makeup preserved a likeness which eventually stiffened and forbade any expression beyond that which had been applied. Penn Face, too, feels a lot like that makeup of Ungit’s priestesses: something that cakes and hardens until it no longer hides merely our insecurities but erases the contours of our true selves. Over time, the falsely constructed self takes up more and more of our lives, and our real selves less and less. We become indistinguishable in a crowd of polished faces, our individuality dissolving into the performance.

That was the revelation I wish I had carried with me at Penn: that achievement, when used as armor, only deepens the wound it tries to hide. Like Orual, we mistake the mask for strength. We learn to lead organizations, ace exams, and fill our résumés, all the while losing touch with the very self those accomplishments were meant to express. We forget, or perhaps have never really known, that our worth is not earned but bestowed; that our identity is found first in the loving gaze of God.

Near the close of the novel, Orual undergoes her long-awaited reckoning. After a long journey of bitterness, accusation, and painful self-reflection, she is finally brought into the house of the God of the Mountain— a Christ-figure she had once doubted and defied. There, she is reunited with Psyche, now radiant and transfigured, “a thousand times more herself” than she had ever been before. In that reunion, Orual learns that even the greatest human beauty and achievement are only preparations for something far greater. As the god arrives, every veil she has ever worn falls away. She feels “unmade,” yet in that very undoing sees her true self restored. For the first time, she sees herself truly, and as she really is: loved, forgiven, and known. ‘Perfection’ gives way to a still greater Perfection, and the face Orual had feared to show becomes the face she is finally given. In the god’s presence, she discovers the truth of which Lewis writes in the final lines: “You are yourself the answer. Before your face questions die away.”

Orual’s climactic question— “How can [the gods] meet us face to face till we have faces?”— becomes not just the turning point of Lewis’ story, but a question for all of us. It is a question about who we are when every accolade is stripped away and every performance dissolved. It asks whether we have lived so long behind a carefully crafted persona that we no longer know the person God created us to be.

When I finally read Till We Have Faces the summer after I left campus, it felt like looking into a mirror I had all this time been avoiding. Lewis’ story showed me that beneath every Penn Face lies a longing; to be known, to be loved without condition, to belong without having to earn it. And that longing can’t be met by another accolade, internship, or headline. It can only be met when we take off the veil and let ourselves be seen by the God who already knows our true face.

And so perhaps I do not have the most typical answer for you on this— on how to break down the Penn Face. There is nothing here about wellness practices, nor can I offer a nifty five-step program. The university already offers a good many resources for addressing stress and burn-out— and these do matter. But what I am offering here is the invitation that changed Orual’s life, and mine: to stop hiding. To dare honesty with ourselves and with God. To resist the lie that worth is earned. At the same time, it is also a warning not to live a life at Penn where your true self, with its doubts, insecurities, and anxieties, is hidden deep down and covered by a mask of self-assurance— only to find, that at the end of your time there, your real self, your true face, was lost somewhere along the way, and you stand now with none at all.

The culture of Penn Face will not vanish overnight. But maybe it can be unlearned—one conversation, one honest word at a time. Reading Lewis taught me that vulnerability is not a defeat but a doorway. The Christian story tells us the same: that when we remove the mask, we do not find emptiness, but Someone waiting for us. There is a strange grace in letting ourselves be seen — not the shame of exposure, but the relief of finally breathing again in the freedom of God’s perfect love. The invitation is simply this: take off the veil. Let Christ look you in the face. And in His gaze, receive the face that was yours all along.

Euel Kebebew is a 2025 College of Arts and Sciences Graduate with a B.A. in International Relations and History. His email is eueltk@sas.upenn.edu.